The “pleasurable excitements” from surmounting (even sometimes not surmounting) psychological obstacles surpass those of life without such restraints. The struggle against adversity which this entails is essential for fulfilling emotional life. While psychologically painful, it was worth the cost, because “the dignity of man consists precisely in his ability to restrain himself from dashing away along the flat, in his capacity to raise obstacles in his own path.” Turning back from those obstacles is often “the most nobly and dignifiedly human thing a man can do.” This resembles Irving Babbitt’s view that “what is specifically human in man and ultimately divine is a certain quality of will, a will that is felt in its relation to his ordinary self as a will to refrain.” For both men, this self-mortification was an act of loyalty to standards, and indispensable for upward self-transcendence. His 1931 essay “Obstacle Race,” published while Brave New World was in progress, depicted nineteenth-century life as “a kind of obstacle race,” with conventions and taboos restricting behavior being the obstacles. Huxley saw self-restraint as essential to human dignity and proper living. Unfortunately, much self-transcendence is horizontal (toward “some cause wider than their own immediate interests,” but not metaphysically higher, from hobbies and family to science or politics) or even downward (toward drugs, loveless sex, etc). We know … that the ground of our individual knowing is identical with the Ground of all knowing and being.” Our mission in life, then, is “upward self-transcendence,” metaphysically upward affiliation culminating in union with the Divinity.

“In a word, they long to get out of themselves, to pass beyond the limits of that tiny island universe, within which every individual finds himself confined.” This longing arises because, “in some obscure way and in spite of our conscious ignorance, we know who we are. Moreover, people possess not only a will to self-assertion but also a will to self-transcendence.

/0060929871_bravenew-56a15c295f9b58b7d0beb140.jpg)

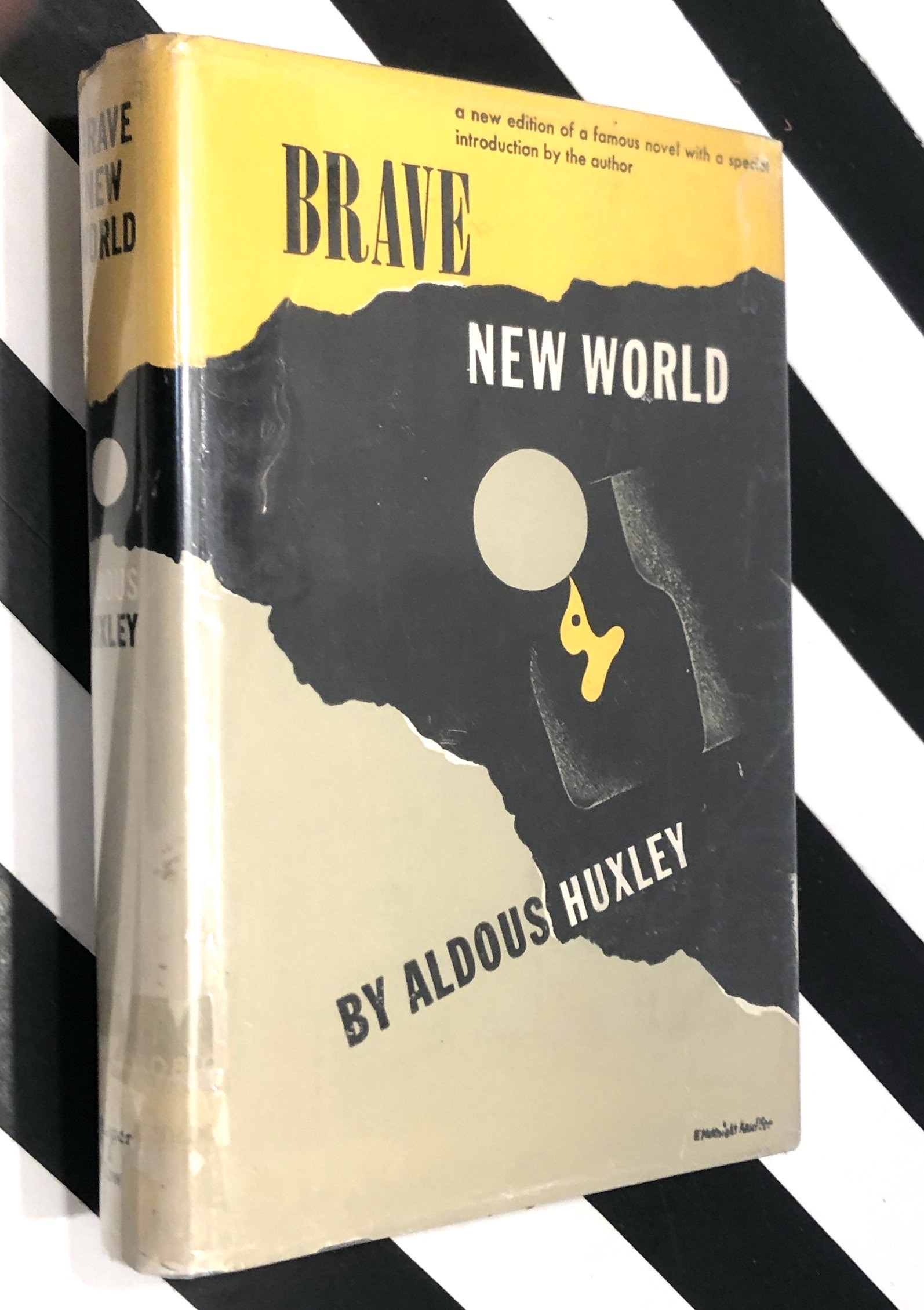

So far from being irrelevant, our metaphysical beliefs are the finally determining factor in all our actions. It is in the light of our beliefs about the ultimate nature of reality that we formulate our conceptions of right and wrong and it is in the light of our conceptions of right and wrong that we frame our conduct, not only in the relations of private life, but also in the sphere of politics and economics. Man, Huxley maintained, is an “embodied spirit.” As such, he is governed by belief: As Milton Birnbaum points out, by the early thirties, Huxley was in transition from cynicism to a mystical religion, which held that a transcendent God exists, and that one’s proper final end, as the foreword to the 1946 edition of Brave New World notes, is “attaining unitive knowledge of the immanent Tao or Logos, the transcendent Godhead or Brahman.” (Indeed, with its religious theme, Brave New World emerges as a milestone in Huxley’s odyssey.) Subsequent history has vindicated his pessimism.īrave New World’ s significations flow from Huxley’s vision of reality and human nature and its implications for proper living. Reading the signs of his times, Huxley saw awaiting us a soulless utilitarian existence, incompatible with our nature and purpose. Huxley himself described its theme as “the advancement of science as it affects human individuals.” Brave New World Revisited (1958) deplored its vision of the over orderly dystopia “where perfect efficiency left no room for freedom or personal initiative.” Yet Brave New World has a deeper meaning: a warning, by way of a grim portrait, of life in a world which has fled from God and lost all awareness of the transcendent. Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) is commonly seen as an indictment of both tyranny and technology.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)